Are the Conservatives running the worst election campaign of all time? Much of the media narrative would suggest as much and the polling would back this up – not just in terms of voting intention but in how people view the campaigning. According to YouGov, 43% of people think that the Conservatives are running the worst general election campaign so far, compared to just 8% for Labour.

Satisfaction levels for Rishi Sunak have reached the lowest levels of any Prime Minister since 1979, according to Ipsos.

The sequence of gaffes and PR disasters continues with the spread of the “gamble-shambles” betting scandal across several Conservative candidates, aides and now at least seven policemen who allegedly placed bets on the date of the election, potentially taking advantage of insider information. YouGov’s AI-powered news tracker shows that the scandal is now getting more awareness than Rishi Sunak leaving D-Day.

As well as the cut-through of these issues, the election is getting wide dissemination. According to More In Common, 82% of people are watching, reading or listening to the news, 71% have received political leaflets and 61% have seen an advert for a political party. Exposure to the election is through the media – just 17% had a political campaigner knocking on the door.

Exposure does not mean engagement, just 20% of people say that they are enjoying the election, compared to 72% who say they are not. It is important for the minority of us that are highly engaged to appreciate that the vast majority are not. As one political pollster put it, the average person thinks about politics for around five minutes each week.

So does that mean that campaigns don’t matter?

Despite the series of negative headlines in offline and online newspapers, angry callers to talk-radio and pundits doing the rounds on political podcasts, not much has changed in the overall polls.

Redfield & Wilton Strategies have produced a very helpful long-view visualisation of the polls over the last four years. The start of the decline in Conservative support can be traced all the way back to the first Covid lockdown and specifically to Boris Johnson’s chief-of-staff Dominic Cummings driving to Barnard Castle while recovering from Covid to ‘test his eyesight’. This started a narrative of “one rule for us another rule for them” that continued through ‘partygate’ and has echoes in the latest betting scandal.

Modern historian Dominic Sandbrook argues in the latest episode of The Rest Is History Podcast (the UK’s most popular podcast with 12 million downloads a month according to Goal Hanger Productions co-founder Tony Pastor) that campaigns rarely change the course of elections and when they do, it is when they feed into an existing perception.

In the 1992 election for example, opinion polls suggested a narrow win for Labour but a combination of negative campaigning around ‘Labour’s Tax Bombsell’ (which is echoed in the £2,000 per person tax rise messaging this time round), and lack of support from the then powerful tabloid newspapers led to a small Conservative majority.

In 2017, Teressa May went for a snap election based on a 21 point lead in the polls. The following weeks saw a relatively strong campaign from the Jeremy Corbyn led Labour Party, particularly on social media, combine with a poor campaign from the Conservatives. Teressa May was exposed as a poor and unrelatable communicator (including her infamous “fields of wheat” story), combined with badly received policies, most notably changes in social-care which became labelled the “dementia tax”. Despite Teresa May pleading that ‘nothing had changed‘, the 21 point polling gap collapsed and the election resulted in a hung parliament.

The emerging narrative was that there had been a “youthquake” with the Labour campaign mobilising previously unengaged young people to vote.

As I pointed out in my previous article on predictive analytics, the facts don’t always support the story. Analysis from the gold standard British Election Study showed that there wasn’t much of an increase in turnout from 18-24 years olds, who continued to be the least likely to vote. The much bigger shift was in middle aged people being more likely to vote Labour than Conservative than 2015.

Another inconvenient fact is that the number of people voting Conservative actually went up – more people voted Conservative in 2017 than any election since 1997. It was the drain away of votes from the smaller parties to Labour and Conservatives that led to the stalemate.

Boris Johnson’s 2019 election win was portrayed as the result of a strong campaign based on ‘Getting Brexit Done’ with Boris doing a ‘Heineken’ and reaching parts of the electorate that other politicians couldn’t reach. And yet the Conservatives increased the number of votes by just 2% and overall turnout actually decreased. It was support for Labour going back to the smaller parties that led to an 80 seat majority.

There was a similar pattern in the 1983 election. The popular narrative is that Margret Thatcher took a feel good factor from the UK’s victory in the Falklands War and combined with a modern US-style campaign to romp to the largest majority since 1945. However the number of people voting for conservatives went down compared to the previous election in 1979. The much bigger factor was the split on the left with moderates leaving Labour to form the Social Democratic Party and form an alliance with the Liberals.

Another myth is the enthusiasm for Tony Blair and New Labour around the millennium. Comparisons between Labour’s position today with New Labour is causing angst amongst political commentators. Despite polling and MRP models showing a landslide next week, there are concerns that the predictions could be wrong because of a lack of enthusiasm for Kier Starmer and Labour, especially compared to New Labour winning their landslide in 1997.

But again the facts don’t fit the narrative. Tony Blair’s Labour got less votes in 1997 than John Major’s Conservatives did in the previous 1992 election. Voting turnout decreased from 78% in 1992 to 71% in 1997 and to just 59% in 2001, the lowest turnout since 1918. And yet these were the years of the largest Labour majorities.

Do you win an election or do you lose it?

“Two men are walking through the forest. Suddenly, they see a tiger. One of the men stops to put on some running shoes. “What are you doing” says the other man, you can’t outrun a tiger”. “I don’t need to run faster than the Tiger” replies the first man, “I just have to run faster than you”.

In the first-past-the-post electoral system it is not the absolute performance of the winning party that counts, it is how they compare against the party that comes second. This is as much about the performance of the party that comes second as the party that comes first.

A regression analysis on 26 elections since 1922 (excluding the 1931 ‘National Government’ election of Ramsey MacDonald which is very much an outlier) shows a very strong correlation (+0.80) between the difference in vote share between the winning and 2nd party and the size of the majority. The correlation is much stronger than that between the winning vote share alone and size of majority (+0.49). This is why the polling lead is such an important indicator.

But we are in unprecedented territory. Of the 26 elections there have been 7 with a majority of more than 100 seats. None of the elections had more than a 15 percentage point difference between the first and second party.

Since 1922, the party that comes second has never got less than a 28% vote share.

For the current election, polls so far have maintained a 20 percentage point lead for Labour over the Conservatives with the later on a 21% share of the vote. If this were carried through into the election, the likely Labour majority is around 200 seats.

In the 1997 election, a week out from Election day the polls were showing an 18 percentage point lead for Labour. The actual result was a 13 percentage point lead with the Labour vote share six percentage points lower than the polls suggested. Despite this fall, Labour still secured a 177 seat majority, the largest majority of any government since the 1930s.

I have updated the Hender Research ™ model from last week based on the latest polls this week.

There has been a slight softening of the Reform intended vote, which is likely to be linked to Nigel Farage’s interview with the BBCs Nick Robinson where he put part of the blame of the war in Ukraine on EU and NATO expansion. Luke Tryl from More in Common suggests this is likely to antagonise traditional conservative voters – 81% of whom sympathise with Ukraine.

The latest model shows an increase in the number of Conservative seats from 97 to 115 and a reduction in Labour’s majority from 226 to 184, much more in line with the 1997 result.

But the results could be very volatile. In the model there are 118 out of 650 seats where the winning candidate is within 5 percentage points of the candidate who comes second. This means that small changes in vote share can make big differences to the number of seats.

Even the typical 3 percentage point error margin of polls can make a big difference. An error margin size swing towards the Conservatives increases their number of seats from 115 to a much more respectable 167 and reduces Labour’s majority to 94. Conversely a swing in the opposite direction takes the Conservatives down to just 49, gives Labour a 306 seat majority and makes the Liberal Democrats the second largest party with their leader Ed Davey becoming the leader of the opposition.

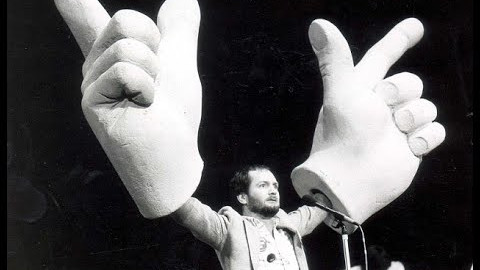

This would be some result for the man who has manfully fallen off paddleboards, gone on roller coasters and performed CPR to the Bee Gee’s Staying Alive, all to get some media attention for his party.