It’s an uncertain world

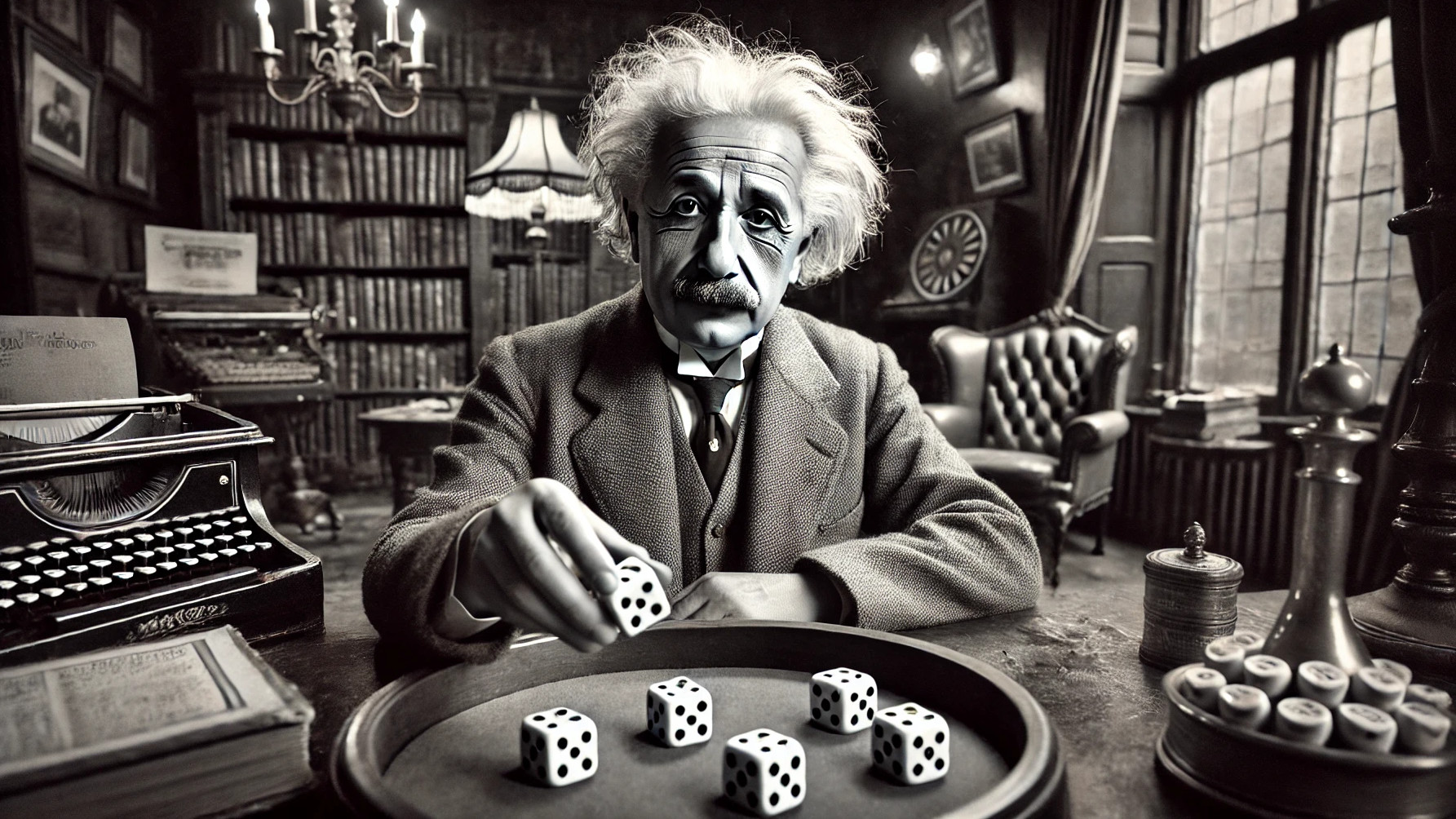

“God does not play dice” Albert Einstein wrote in a letter to fellow physicist Max Born before the 1927 Solvay Conference on the emerging science of Quantum Mechanics. An event my son described as the “Avengers Assemble” of physicists.

The resulting Copenhagen interpretation that the world is underpinned by random events and probability did not fit with Einstein’s belief that the physical world was subject to predictable rules. The Copenhagen interpretation became the established consensus and Einstein was seen as yesterday’s man.

The mathematics of probability and prediction developed several centuries earlier and was very much related to dice. Pioneering mathematicians such as Pascal and Fermat developed much of the underlying theory, often to help French Aristocrats improve their fortunes at gambling.

Sports and gambling leads the computer revolution

On a similar theme, much of modern predictive analytics was pioneered by gambling and sports. In the 1970’s Davey Johnson, the manager of the Major League Baseball team Baltimore Orioles, used a computer simulation written in FORTRAN on his boss’s IBM Mainframe to predict game outcomes based on different batter lineups.

This led to the emerging, and very specific, science of Sabermetrics – using statistics to predict better outcomes in baseball. This approach was refined and optimised by the Oakland Athletics in the 1990s, made famous in Michael Lewis’s book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game.

The 1990’s also saw gambling becoming digitised. In 1994, the online betting company Microgaming launched the first online casino. The business used the theories of Pascal, Fermat and Bernouilli (such as the ‘law of large numbers’) to leverage the larger reach of an online service to further tip the odds in favour of the house always winning.

Big data goes big

The increasing scale of audiences and the rise in computing and database power led to companies further developing predictive analytics for commercial gains. Amazon was founded in 1994 as an online bookstore. In 2003 researchers Greg Linden, Brent Smith and Jeremy York developed an algorithm called Collaborative filtering to recommend books to a user, predicting what they would like based on other users similar purchasing habits.

In 2012, the New York Times published an article headlined ‘How Companies Learn Your Secrets’ based on a conference talk given by Andrew Pole, a statistician who had joined the retailer Target in 2002. His team’s data science work claimed to be able to give a reasonable prediction of whether a woman was likely to be pregnant based on her buying habits.

The article told the story of a man who complained to the manager of his local Target that his school-age daughter was being sent coupons for baby clothes. The man returned several days later to say “It turns out there’s been some activities in my house I haven’t been completely aware of. She’s due in August. I owe you an apology.”

Unfortunately the story, subsequently appeared to be precisely that, a story. There was no evidence it had come from Andrew Pole’s work, the man was never named. It was one unattributed anecdote in a single newspaper article. As the Chief Financial Officer of a former business once said to me: “never let the facts get in the way of a good story”.

Like all good stories, it spread. In the following years, businesses across all sectors experienced a Fear-Of-Missing-Out in the adoption of data science, machine learning and AI. As the former chief scientist at Amazon said “mathematicians are suddenly sexy”.

AI and Predictive Analytics in Comms

In PR and communications, the adoption of data science and predictive analytics has been a mixed picture.

Burson recently launched the Fount Suite which utilises AI to improve automation and analytics. Allison Spray, Group Managing Director for Data and Intelligence was on the panel of the Evolution of AI in Comms PRCA event this week and spoke about the opportunities for AI and data science, including in predictive analytics. Allison is walking the talk having recently completed a postgraduate degree in AI at Oxford and leads a team of data scientists, analyst and behavioural scientists who are working on further innovations.

However, more broadly, predictive analytics is not widely used in the communications industry. According to the last AMEC survey, just 20% of AMEC members were using predictive analytics in their business in 2023, down from 23% in 2022. This compares poorly to other uses of AI such as topic identification (78%), entity extraction (65%) and automated sentiment (58%).

From Sabermetrics to Politics

Political forecasting has developed to become an industry in its own right. Nate Silver, took his experience in using sabermetrics techniques in predicting Baseball outcomes to predicting political outcomes. The election forecasting system he developed successfully predicted the outcomes in 49 of the 50 states in the 2008 US election. In refining his model he predicted the 2012 and 2020 presidential elections and gave Donald Trump a higher probability of winning the 2016 election than many other forecasts.

In 2017 YouGov developed a MRP methodology (Multi-Level Regression with Post Stratification) to predict the outcome for that year’s election. MRP models use much larger data sets than traditional polling and use a combination of socio and demographic factors to better predict how a national vote share will apply to specific constituencies.

Unlike most polling companies, the MRP model correctly predicted a hung parliament that year. YouGov’s MRP model also correctly called the 2019 UK election.

For the 2024 election, several polling and research organisations have developed MRP and other predictive models. In the last week there have been several new model releases. While there is some variation, they are all pointing to broadly the same result: a huge majority for Labour and a decimation for the Conservatives.

For fun, I have dusted down the non-MRP model that I built for the 2019 election, updated it with some new assumptions and plotted it against the professionals

Prediction affects the prediction

One of the more spooky things that came out of the Copenhagen Interpretation was the principle that in quantum mechanics the very fact of measuring something affects its behaviour.

This has a very real world problem in the development of quantum computing which many experts are believe to be essential to keep up with the increasing demand of computing power needed for AI.

It is also a useful analogy in how predictive analytics can itself affect the probability of the outcome.

This election is a good example. Most of the polling companies rely on the publication of their polls, not least because they are often used a marketing tool to sell market research to commercial organisations. Many have exclusives or are affiliated with media outlets: YouGov through Sky, Ipsos with the Guardian, More in Common with the News Agents podcast, Savanta with the Telegraph.

The polls and MRP seat predictions have generated a huge amount of interest in the media and this has led to politicians having to respond to expectations when being interviewed. Defense Secretary Grant Shapps appeared to admit defeat on an interview on Times Radio saying that the conservatives may lose but it was important for labour not to have a “supermajority”, which isn’t even technically a thing in the UK system.

Not a single vote has been cast but already there is concensus narrative that Labour will win, it is just a case of how much. Conservatives appearing to throw the towel in could make things worse. But it could have the opposite effect with many people not bothering to vote because they think it is a forgone conclusion. Younger people are less likely to vote and younger people are overwhelmingly likely to vote Labour, so this could lower the Labour vote.

A likely Labour landslide is reflected in the betting markets with odds of 1:20 on a Labour Majority, the equivalent of a 95% probability. This is close to the current prediction from the Electoral Calculus model which shows 94%. This means that in one in 20 times you would not expect a Labour Majority.

To add a drop of jeopardy, it is worth pointing out a recent example of probability estimation from the current T20 Cricket World Cup. CricViz, the cricket analytics company, gives live updates in the probability of the outcome during matches. In the flagship India vs Pakistan match, Pakistan were predicted a more than 90% chance of winning, more than three quarters of the way through the match. They lost.

One thing that is certain now is the date of the election. Unfortunately a group of people around the Prime Minister appear to have been certain about this before the rest of us and placed bets on the date of the election, a few days before the date was officially announced. They are now being investigated by the Gambling Commission.

Cabinet Minister Michael Gove said the situation “doesn’t look great”. By improving their odds of winning a bet, they may have reduced the odds of winning overall.